Acknowledging suicide to be a public health crisis and crafting nation-wide strategies should be the first big step.

There are three things that really…,” Dr Lakshmi Vijayakumar, a Chennai-based psychiatrist working on suicide prevention, pauses to search for the right word. Frustrate? “Yes, three things that really frustrate me. One is the lack of political will to address suicide prevention,” she says. The others are the high number of youngsters dying by suicide in India, unlike in the West, and the growing number of women among them. Vijayakumar, a member of the World Health Organisation’s network on suicide research and prevention, puts it bluntly: “There is no other condition in India that causes the loss of 2.3 lakh lives a year, and nobody does anything about it.”

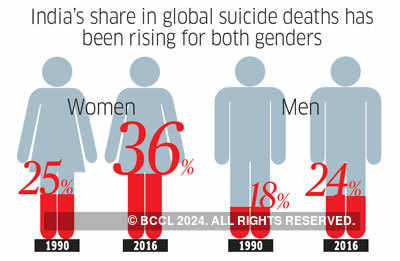

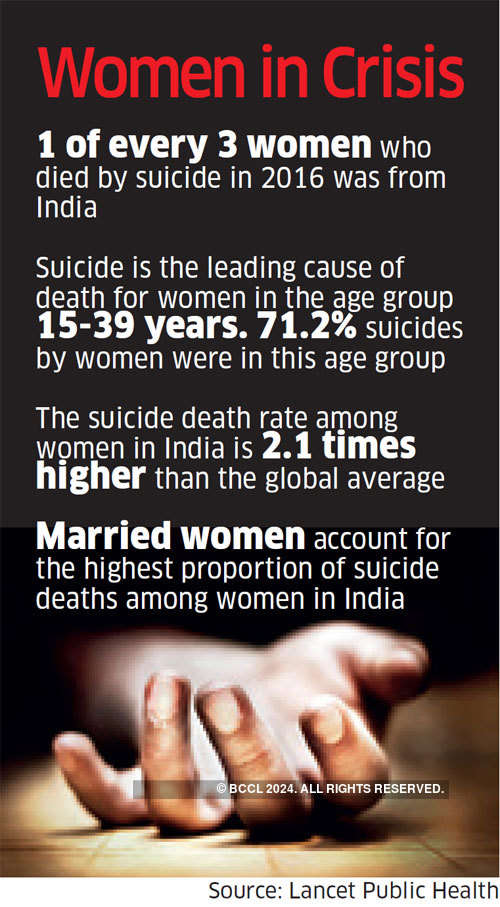

Vijayakumar’s concern is understandable. Data released recently by the online journal Lancet Public Health, as part of its Global Burden of Disease Study (1990 to 2016), revealed, for the first time, the quantum of the problem India is facing: in 2016, it had the highest number of suicide deaths. The country’s share of the global number ofsuicide deaths has been rising, both for men and women. One of every three women dying by suicide, the report revealed, is from India.

The numbers came as a surprise because so far India has mostly relied on annual figures released by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). NCRB pegs the number of suicide deaths in 2016 at 1.3 lakh, close to half the Lancet Public Health figure of 2.3 lakh.

The disparity, says Rakhi Dandona, one of the lead authors of the report, is because suicide deaths are under-reported in India, particularly because it was held to be a criminal offence until 2017 (Please check: the act was passed in 2017, I think). The data shows that the number of suicide deaths in India were higher than deaths related to AIDS (62,000 in 2016) or maternal mortality (45,000 in 2015). In short, it is a public health crisis though it is not being addressed as one.

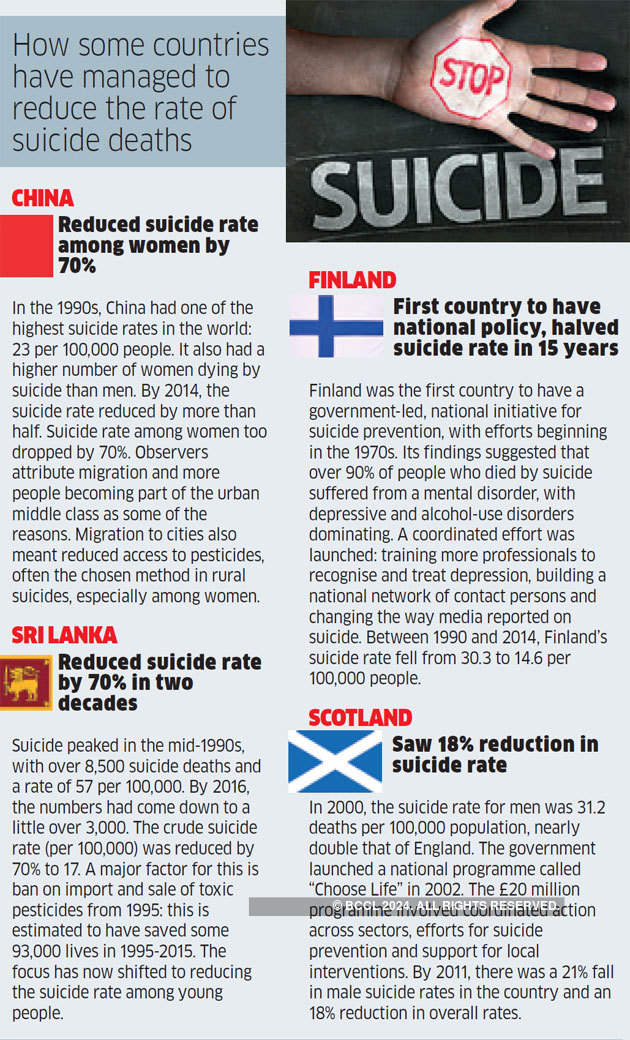

One reason for the reluctance to tackle it could be that suicide is a complex problem, with a myriad factors leading to it. Interventions cannot be as straightforward as with polio, for example, vanquished through countrywide immunisation programmes and widespread awareness. Nor is it something that states can afford to wash its hands of, on the grounds that it is a “personal issue”. There are countries that have implemented national suicide prevention policies, which have met with at least some success (See “How Some Countries...”).

“The biggest misconception around suicide is that it is not preventable and that those who die have already made up their mind. This is far from the truth,” says Nelson Vinod Moses, founder, Suicide Prevention India Foundation. Nine out of ten suicide survivors don’t die by suicide and seven out of ten don’t make a second attempt, he points out. Recently, he had been able to successfully counsel a 19-year-old college student who reached out, saying she wanted to end her life because her ex-boyfriend was threatening to release some personal pictures online. “I told her she need not feel shameful for what had happened and that she should continue her course in computer science, get married to someone else and have a family.” Moses also encouraged her to confide in her parents and overcome the guilt she was feeling, a common emotion among youth contemplating suicide.

Restrict Access This also ties in with another aspect of suicide in India: it is not always linked to mental health and hence needs to be addressed accordingly. Dandona, a professor at Public Health Foundation of India, says the NCRB data alone would show that the biggest causes cited are personal and social problems such as love affairs or issues with families. “You can’t change this by making it part of a mental health programme,” she reasons. Even in the case of farmer suicides, the underlying factor is financial crisis, she says.

“There are effective interventions but nobody seems to be willing to address them,” says Vijayakumar. One of the “lowest hanging fruits” in suicide prevention, according to her, is restricting access to pesticide, which is commonly used to die by suicide in rural areas. It has been established that easy availability of lethal means is an important factor in suicide deaths. For instance, one reason why suicide deaths among rural women in China have come down is because when they moved out of villages, their access to pesticides — a common method — was also limited. Sri Lanka, too, saw its suicide death rates reduce after it banned the import and sale of toxic pesticides. In Australia, firearm suicides declined after the gun law reforms of 1996, when certain kinds of firearms were banned and there was a compulsory buyback.

Similarly, India could restrict access to pesticides. In two villages in Cuddalore in Tamil Nadu, Vijayakumar initiated a WHO-funded project from 2010 where pesticides were stored centrally in lockers, instead of in farmers’ houses, thereby restricting access. The number of suicide deaths in the intervention site came down from 2 in 2011 to zero every year till 2017 while the number of attempted suicides declined from 3 in 2010 to zero in 2017.

The Tamil Nadu government in January decided to spread the programme to 100 villages. The centralised storage is also set to be replicated in 60 villages in Gujarat, as part of a multi-agency research partnership called Suicide Prevention and Implementation Research Initiative (SPIRIT), along with training of students to cope with psychological distress and of community health workers to identify people with suicidal tendencies and refer them.

Moses suggests that more people should be encouraged to undergo the WHO-endorsed QPR (Question, Persuade and Refer) Gatekeeper Training online, in which people are taught to understand warning signs, identify risk factors and persuade someone contemplating dying by suicide to seek help. “It comes from the premise that suicide prevention is everybody’s business. But though it is a low-cost method, less than 1,000 people in India have taken it,” he says. This may be changing. A retail chain recently got in touch with Moses’ foundation to help train all 12,000 of its employees; colleges, too, have expressed interest.

While these efforts would help, so would a national suicide prevention policy, which could address the population as a whole and also include targeted interventions, say public health experts. The Lancet Public Health study, which reveals the wide variation between states when it comes to suicide rates highlights the need for state-specific, targeted interventions. For instance, Tamil Nadu had the highest suicide death rate for women, at 25, while Mizoram had the lowest, at 2.5 (per 100,000 population). “That’s a huge difference. What this means is that while we need a national policy, we will also need to tailor it to the needs of each state,” says Dandona. A well-drafted policy would help increase awareness about suicide prevention, reduce stigma, increase collection of data and lead to responsible media reporting, among others, says Moses. The infrastructure is also woefully inadequate, with only 44 helplines across the country, of which only nine are 24x7 and none of them is connected by a single helpline number.

While decriminalising the attempt to suicide was a welcome first step, India will need to do a lot more, if it wants to tackle the highest cause of death among its youth and the ninth biggest cause of death in the general population. Acknowledging it to be a public health crisis and crafting nation-wide strategies could be the next.

If you have suicidal thoughts, seek help immediately. Helpline numbers: Sneha India: 044-2464 0050/044-2464 0060; help@snehaindia.org. Connecting India: 18002094353, 9922001122 -- TISS icall: 022-25521111 (Monday to Saturday, 8 am to 10 pm)

Credit: Article by Indulekha Aravind, ET Bureau dated Oct 14, 2018

Related Article

'Suicide is not just a mental health issue'

READ MORE:

Sunday ET|suicide deaths|suicide|public health crisis|india suicide cases|Farmer suicide

No comments:

Post a Comment